The Definitions Book is Divided into Four Parts:

Using Words You and Your Audience Know

What Happens When We Communicate

The Importance of Defining Terms (part one)

The Importance of Defining Terms (part two)

What is a Definition?

The Various Types of Definitions

Types of Definitions Cheat Sheet

How to Test Existing Definitions

Step 0 - Limit your definitions to a single concept

Step 1 - Research the Term

Step 2 - Determine the Term's Concept

Step 3 - Choosing the Definition Type

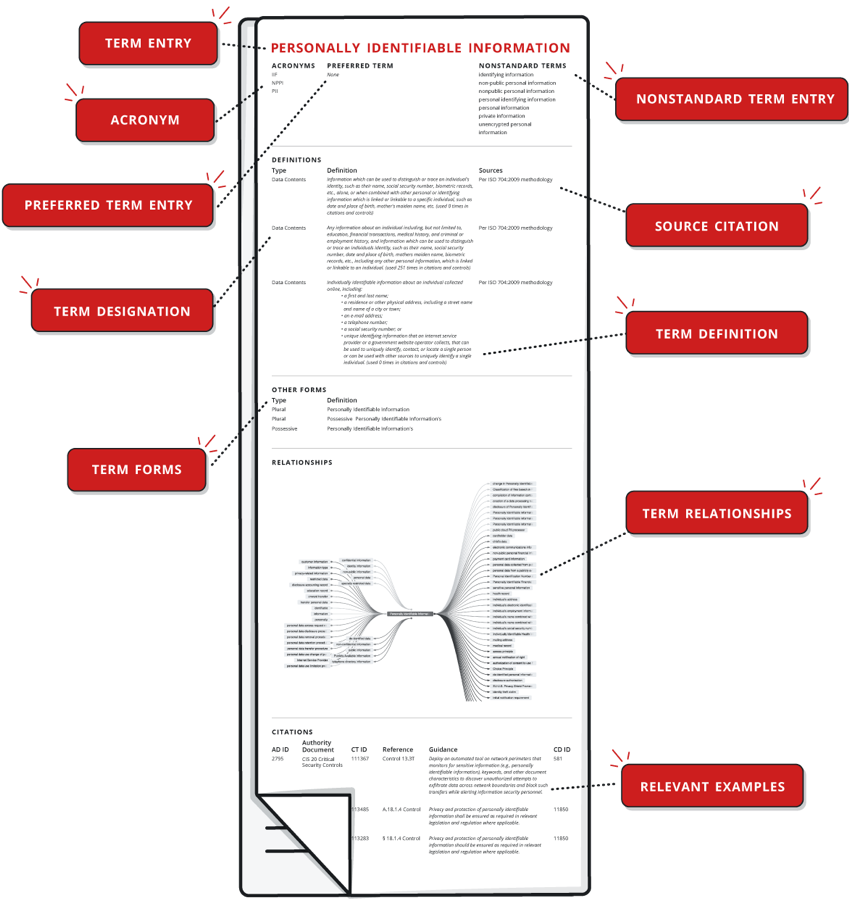

Step 4 - How to Formalize the Term Entry

Step 5 - Add Semantic Relationships to the Definition

Step 6 – Reviewing Your Definitions

What are Conversational Entries?

What are Snippet Entries?

Glossary Entries

How to Automate Glossary Creation

What are Dictionary Entries?

Bibliography

Before we get into how to write a definition, you need to know a bit about definitions themselves, and how to spot good and bad definitions.

Once you know that, we’ll walk you through the five steps to creating a good definition.

Then we’ll teach you how to apply and extend those steps to craft different types of definitions.

So let’s start at the very beginning, shall we?

Ya know, this seems pretty obvious – almost so obvious it shouldn't be the first thing you read in a book about how to write definitions. But it has to be said. It has to be said because all too often we read something in our business lives (not so much for entertainment, thank the universe) that just doesn't make sense. In some instances, the author wants to "sound smart" by using "big words". As an example, here's a student’s paper that I read the other day:

"The dialectical interface between neo-obstructionists and anti-disestablishment GOPers is stuck in a morass of quibbling over pettifog."

The paper was about discussions between students and lawmakers over stricter gun laws for assault weapons. The sentence, in plain English, reads as this:

"The logical discussions between student protesters and Republican lawmakers resisting change are bogged down because of arguing over petty things."

In some instances, the author just uses the wrong words. One famous example, used in many word choice articles, is as follows:

"Cree Indians were a monotonous culture until French and British settlers arrived."

What the author meant was that Cree Indians were a homogenous culture.

So, before we get started on a conversation about definitions, when picking your words, if you run across words you don't use often, ask yourself these basic questions:

1. Can I spell the word correctly? Here's a hint: Open your favorite word processor and make sure active spell-checking is turned on. Then type the word. If it comes up with an underline, your dictionary doesn't recognize it. Most word processors will allow you to Control-Click or Right-Click the term and look up a spelling suggestion.

2. What does this word mean? Second hint: Research the term online and find a consistent meaning. If you can't readily find a definition for the term don't use it. Try looking up the definition of "dialectical interface" above. If you find a definition, email the team at info@unifiedcompliance.com. We'd love to see it and know where you found it.

3. Will the people I'm communicating with know what this word means? Will they have the same understanding of the meaning that I do? Third hint: Ask a few people who might read your writing if they know what your term means. You'll be surprised at the varied answers. We did this once with government writers working on a cybersecurity manual. We asked for the definition of Cybersecurity. Twelve people, thirteen answers - all different. One guy wrote two answers because he wasn't confident of either one of them.

If you don't know what you are talking about, no one else will either.

To understand what's happening when we communicate, we need to understand what a concept is, what a term is, and what an instance means. Let's start this discussion with a quick illustrative point.

You and I are sitting at a table. In front of us is the plate in the diagram that follows. One of us is from Chicago, the other from London. I say to you, "may I have a biscuit?" Your answer is "of course". I then pick up which item(s)?

If I were from Chicago, that plate would contain one biscuit and two cookies. If I were from London, that plate would contain one scone and two biscuits. What's going on here is:

The concept of the big, soft, flaky, doughy thing has generally been given the term scone in England and biscuit in the US. The concept of the drier, smaller, crunchier things has generally been given the term biscuit in England and cookie in the US. When I asked for the biscuit, I've identified the term and the conceptto me. It's when I reach for the biscuit that I tie the instance and the name together for both of us.

And that's where the fun starts. You look at me and say, "hey, I thought you wanted the biscuit/scone" (depending on where you are from). I would explain, "yes, and I took one". We would both be baffled at the lack of the other's comprehension of what we know to be true.

If we were friends, we'd probably continue with "I thought that was called…" and then add the term that goes with the concept in our mind. A quick sharing between us would bring out both concepts, both definitions of what we think we are looking at. And we'd do the same, probably, for the cookie/biscuit concepts of the instances we see.

This is why it is important to know how to write good definitions, but more on this later. We took an instance from reality and stated the term we have given to the definition of its concept. We have, for one bright shining moment, communicated with each other. Being from Chicago, while living in London for a period of time, I ended up simply using the definitions of things I'd point to; "can I have one of those fluffy pastry things there…" I'd ask at the bakery.

This is why defining your term is important.

There is a quote attributed to George Bernard Shaw that follows along the lines of, "Britain and America are two nations divided by a common language". Whether or not the attribution is or isn't Shaw's, the point is that even though we use the same words, those words can (and often do) have quite distinctly different meanings because of our cultural differences1. There's even a British English vs. American English translation dictionary2!

To put it short and sweet - words, the terms we use, do not have one correct meaning. Words can mean different things at different times. They come into existence to express thoughts by a group of people that share them, at a point in time, with a meaning that reflects their origin, use, and timeframe.

Take, for instance, the word awful. Originally, that word meant "worthy of awe", as in "very inspiring". However, over time it has come to mean bad, displeasing, offensive, etc. A quick Google search will produce list upon list of terms that have changed over time3. More specifically, the words and phrases that you find in a dictionary exist to express these shared thoughts, which we'll refer to as concepts throughout this document.

We won't go into the philosophical debate of whether concepts define words or words define concepts, a debate that is currently plaguing educators today4, as it has been since the times of Plato and Socrates5. Nor will we spend time debating about specific definitions of terms, how the definitions morph over time, or the nature of, and demands on, definitions6.

Instead, this document will focus on how to fulfill the need to establish and maintain definitions for specific terms within specific subject fields7. There is an entire international standard dedicated this pursuit8, from which we have drawn much of our inspiration. The issue we are attempting to remedy in this document, is the tendency of each subject field to create its own sub-language of specific terms and their definitions. These terms might be shared with other subject fields, but quite often the definitions for these shared terms are different. And just as often, those in specific subject fields create new, distinct terms used to describe the same concept as other terms found in other subject fields. So, we end up with this:

Same words - different definitions.

Same definitions - different words.

If you want a real-word example, perform this Google search:

What is personally identifiable information?

The last time we performed this search, Google returned over 1.7 million entries with well over 100 definitions (we stopped counting about then)9. With this huuuuuuge list of potential definitions for a key term such as Personally Identifiable Information, you have to agree with us that the only way you can share your meaning is through how you use the term. Better yet, you can provide a definition for the key terms you are using. In short, if you define your key terms, you'll clarify the concepts behind the terms you are using in that argument, in that document you wrote, or if they are added to some custom dictionary, in that specific field the dictionary covers.

Yes, certain words have multiple meanings. We've covered the reason to define which meaning you are using if you think those you are communicating with will be befuddled. That's one reason to define what you are saying. The other is when you are creating new words. And let's face it - we do that more of-ten than you'd think.

When we wrote about using words your audience doesn't know it was because we were pointing out you didn't know either. If you find yourself in a place where you are using words that others don't know - look up those words to see if someone has given them a definition. Look it up online and find a consistent meaning. If you can't readily find a definition for the term, then define it! Where do you think dictionary definitions come from? You. Me. Them. Everybody! (Everybody, needs somebody! Everybody - needs somebody to define! he laughingly sings...)

Dictionaries are historical references There. I said it. But more importantly, so did John Simpson, former Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. Here's a passage (edited for clarity) from a book he recently wrote10:

"It is easy to be too precipitate in selecting a word for inclusion in the dictionary… In general, we learned to shy away from trying to define any new word – wherever possible -- until it had a chance to settle down in the language...it is helpful for us to see whether others publish preliminary accounts of the word from their own impressions or research. That's not cheating; it's just good research sense."

The simple point is this - if you want to use a term you can't find a definition for, you need to write that definition. And the great part is, if it is your word, your definition can't be wrong! These types of definitions are called Stipulative definitions, and we'll cover them in a bit.

In its simplest form, a definition is “a statement of the meaning of a word or word group or a sign or symbol1”. In other words, a definition explains through clarification and further explanation what we are trying to say with one or a few short words. Aristotle would say that the definition provides the essence (ὁρισμός horismos) of the term2.

Well, that’s nice, but it isn’t that helpful unless you are a philosophy major who can spout out what essence means as part of dinner conversation. And even if you wanted to we’d rather you just stare blankly at your iPhone.

So, to start this off, let’s look at an example of a bad definition, one that just doesn’t fit the essence of the term it is supposed to describe. In our research we come across a great deal of bad definitions, many of which are found in published glossaries.

For example, a technical glossary from the United States’ National Institute of Standards and Technology, their Glossary of key Information Security Terms, defines the term Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT) as - a capability set up for the purpose of assisting in responding to computer security-related incidents. This term, absent of the definition, and because it describes a team, brings to mind a group of people who respond to computer security incidents. However, the presented definition egregiously leaves out the entire essence of team and replaces it with capability. Although the team in this definition should be comprised of individuals who possess the capability to respond to security incidents, the definition fails by mistaking a group for a capability.

How to format a well-written definition

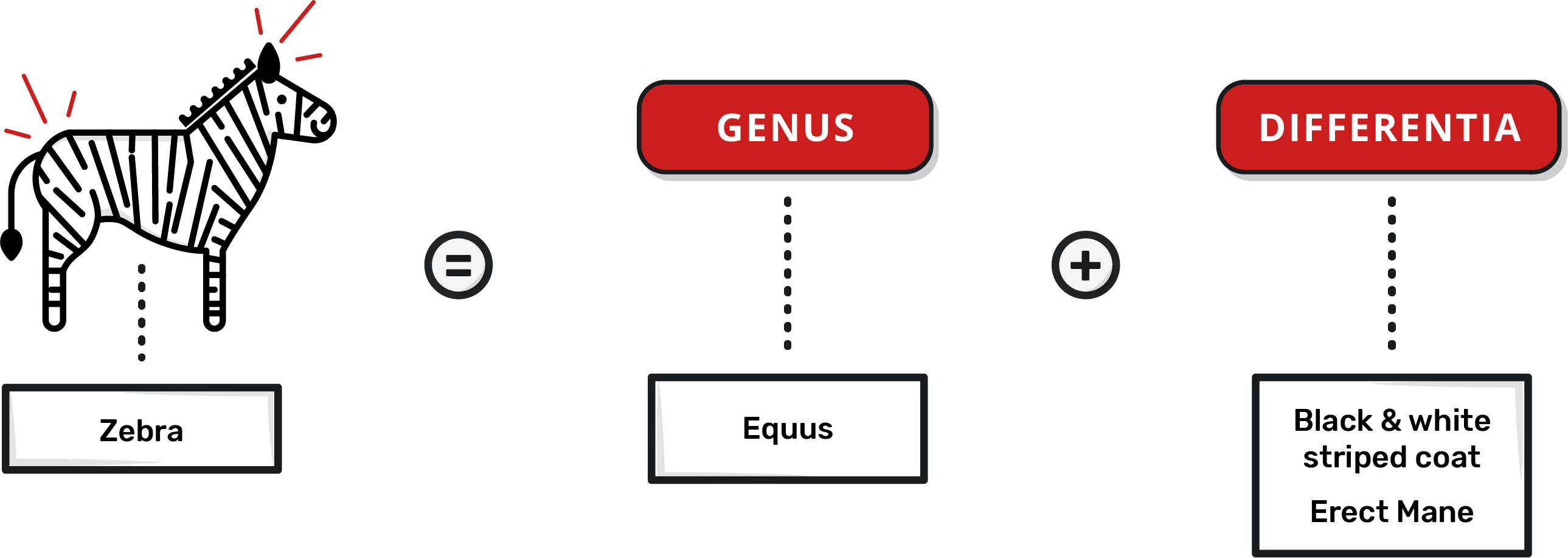

All of the reading we’ve done, all of the research we’ve done, except for Purdue’s Online Writing Lab example13 (which states you need to always start with the term, which we will ignore), breaks a definition down (roughly) into two parts, as shown below:

category of concept + differentiating characteristics

Or if you like to use scientific words:

genus + differentia

Category (genus)

This defines the category or class your concept fits into. In essence, you are relating the term to its broader category so that your audience says, “yeah, I know what those are”.

Differentiating Characteristics (differentia) These are the specific characteristics that set your term apart from other terms within that category. Once you’ve related your term to the broader category, now you are saying “well, it’s like those things, but with these differences.”

Most often, the category of the concept is presented first, followed by the differentiating characteristics. Other types of definitions will lead with what differentiates the concept and then show how it fits into the broader category. The best way to bring this point home is to give you some examples of the different types of definitions that are out there, using terms that we should all be familiar with. By doing this, we’ll be able to give you the definition and then point out how it was formulated.

Let’s say that we were going to describe a Zebra using this method. We would say that a Zebra was a mammal in the family of Equidae (Equus) with black and white stripes and an erect mane.

If this were a conversation, you might be stating it like this; “Hey, you know what a horse is, right? Well this is in the family of horses, but they Zebras have black and white striped coats and short manes that stand straight up.” You are equating it to something they know and then adding the differences for this particular concept or thing. This is the basic form of a definition.

Of course, folks can’t leave well enough alone, so they’ve created several kinds of definitions that you can either delve into or skip over.

The wild thing about definitions is that there are many different types of definitions, each used to explain a particular type of concept. However, the two most general types of definitions are intensional and extensional definitions.

What are the two general kinds of definitions?

There are specific types of definition forms we’ll cover in a minute. But first, we need to start with the most used forms of definitions, intensional and extensional. Let’s look at defining what we see in the illustration that follows:

Intensional definitions

An intensional definition specifies the necessary and sufficient set of features or properties that are shared by everything to which it applies.

| Term | Definition |

| Baked Goods | Foods that are cooked in an oven of some fashion that uses prolonged dry heat, and are usually based on wheat flour or cornmeal. |

In this first definition, we see that the category portion of the definition is “foods that are cooked in an oven”, followed by the differentiator of being “based on wheat flour or cornmeal”. It is both necessary and sufficient for anything being baked to be cooked in an oven of some fashion.

Intensional definitions are best used when something has a clearly defined set of properties and hastoo many referents to list in an extensional definition. For instance, you would want to use an intensional definition to define business records, as a business record is a document (hard copy or digital) that records a business dealing. To attempt to enumerate each and every type of business record would be nearly impossible.

Extensional definitions

The opposite of an intensional definition, an extensional definition is usually a list naming every object (or at least enough of a list to create clarity in the reader’s mind) that belongs to the concept.

| Term | Definition |

| Baked Goods | Breads, cakes, pastries, cookies, biscuits, scones, and similar items of food that are cooked in an oven of some fashion. |

This example presents the individual differentiators first (“breads, cakes, pastries, cookies, biscuits, scones”) that belong to a common category, “cooked in an oven”.

Beyond the two basic types of definitions, there are several other notable definition types that can be employed. We’ll cover them now.

What are stipulative definitions?

This is used when you make up a term for the first time. This means that you’ve completed all of the research necessary and can’t find that term anywhere. It is your assignment of meaning to your term. The illustration below shows two scones, a plain scone on the left and a Charlotte’s Sprinkle Scone on the right.

| Term | Definition |

| Charlotte’s Sprinkle Scone | A baked vanilla flavored scone, dusted with sugar, covered in chocolate sprinkles both baked in and rolled onto the top of the scone. |

The stipulative definition here begins with the general definition of scone – the category – and then adds the differentiator, or specific characteristics of this particular type of scone.

What are lexical definitions?

This is how the term is used in a particular community (think Urban Dictionary), or many of the definitions in Compliance Dictionary that are derived from usage in a single document. In this case – let’s say that the document was Charlotte’s Cookbook – the stipulative definition and the lexical definition could be one and the same, as probably no one else would name their scone Charlotte’s Sprinkle Scone.

| Term | Definition |

| Charlotte’s Sprinkle Scone | These wonderful scones are made with

|

Most definitions in cookbooks, like this one, will start with the category of the item, “scones”, and then the rest of the definition, the differentiator, will be a listing of ingredients. One of our collective favorite recipe sites, Epicurious, follows this format quite often. They’ll describe, in general (the category) what is being cooked, and then provide the differentiator – not only in ingredients, but several versions of the ingredient lists for variations of the food in question.

However, there are other times when industry-specific terms are used in various documents, where you’ll get each of those documents giving their own, particular, definition of the term. Take, for instance, the term retail payment system. Within the United States’ banking world, the FFIEC defines a retail payment system one way. Within the European banking system, the European Central Bank defines it differently, with the European definition being more precise.

| Term | Definition |

| retail payment system | A system that transfers funds between non-financial institutions. (US’ FFIEC) |

| retail payment system | Funds transfer systems which typically handle a large volume of payments of relatively low value in forms such as cheques, credit transfers, and direct debits. They are generally used for the bulk of payments to and from individuals and between individuals and corporates. (European Central Bank) |

Notice that both of these definitions provide the category first, “systems that transfers funds” and “funds transfer system”, and then follow that with the differentiator: “between non-financial institutions” and “handle a large volume of payments of relatively low value in forms such as cheques, credit transfers, and direct debits”.

While these lexical definitions are fairly close, there are other lexical definitions that are very different. For instance, a common term used in many laws is covered entity. Generally speaking, that’s any person or organization covered by the particular law. Two examples show how the US healthcare law called HIPAA, defines the term and how the US New York State defines the term:

| Term | Definition |

| covered entity | Healthcare providers who transmit health information. (HIPAA) |

| covered entity | Any Person or organization operating under or required to operate under a license, registration, charter, certificate, permit, accreditation, or similar authorization under the Banking Law, the Insurance Law, or the Financial Services Law. (New York State) |

Each document has a specific audience they are writing to. Each document has defined the term for the readers of that document. What both of them share in common is the format of the definition. Both start with the category of “healthcare providers” and “any person or organization” and then provide the differentiator after that: “who transmit health information” and “operating under or required to operate under a license, registration, charter, certificate, permit, accreditation, or similar authorization under the Banking Law, the Insurance Law, or the Financial Services Law”.

Here are a couple of different takes on writing a definition that you’ll see sometimes, the partitive definition and the encyclopedic definition. To show the differences, we’ll define yeast, first as a part of something, and then provide a more, exhaustive, definition.

What are partitive definitions?

These are definitions that explain the concept as being a part of a greater whole; the distinct part(s) of a more comprehensive concept.

| Term | Definition |

| yeast | As a key ingredient for most baked goods that is commonly used as a leavening agent in baking bread and bakery products. |

Notice here that this definition begins by saying that the yeast is “a key ingredient”, or part of the category “baked goods”, then adds the differentiator for the part it plays: “leavening agent”.

What are functional definitions?

These are definitions that explain the actions or activities of the concept in relation to the more comprehensive concept.

| Term | Definition |

| yeast | An ingredient that is commonly used as a leavening agent in baking bread and bakery products. |

This definition focuses on what yeast does within the baking process.

What are encyclopedic definitions?

These are definitions that go beyond the requirements of definition. Not only do these types of definitions provide the context and characteristics of the concept, they provide additional information about the concept as well.

| Term | Definition |

| yeast | As a key ingredient for most baked goods that is commonly used as a leavening agent in baking bread and bakery products, where it converts the fermentable sugars present in the dough’s gluten into carbon dioxide and ethanol, thus trapping the releasing bubbles of gas into the gluten and making the dough fill up like a balloon as it rises. |

As with the partitive definition, this definition begins by saying that the yeast is “a key ingredient”, or part of the category “baked goods”, then adds the differentiator for the part it plays “leavening agent”. It then goes on to add how yeast works to make the dough rise as part of the definition. You don’t really need to know how yeast works to understand that it’s a leavening agent, unless you don’t know what a leavening agent is and don’t want to look it up.

What are theoretical definitions?

A definition that is really a scientific hypothesis in disguise. It attempts to present an argument for a concept. Here’s a rare and I think erudite theoretical definition of a US scone that we found.

| Term | Theoretical Definition |

| American scone | A scone in America is a derivative of the British scone with the following differences that have occurred because of time and mannerisms. The American scone has twice the butter-to-flour ratio as the British Scone. It is also normally chock-full of little bits of lovely, such as currants, chocolate nibs, etc. This has occurred because of the incorrigible need for inclusiveness in the American persona. They tend to blend everything and include everything in everything. It seems “more is better” applies not just to their life, but to their baking world as well. |

Notice in this definition that it begins with including the American scone in the category of British scone, and then adds the differentiators of “butter-to-flour ratio” and being “chock-full of little-bits of lovely...”. After the category and differentiator, the definition attempts to provide a theory of how the differentiation came to be.

Useful? Who knows.

Humorous? Yes.

What are synonym definitions?

Then there are the very simplistic synonym definitions. These definitions use synonyms of the concept to describe the concept. They are normally used when you need to define instances of a concept in a simple fashion.

| Term | Synonym Definition |

| biscuit | A British version of an American Cookie. |

| cookie | An American version of a British biscuit. |

Okay, we’ve gone over all of the various types of definitions. You’ll want to keep this cheat sheet around so that you have a shortened version of what should go into each type of definition.

Begins with the category, or properties and features shared by other concepts or things like it.

Continues with what makes this concept or thing different than the other members of its category.

Lists as many objects, properties, or features as necessary that represent the concept or thing being described.

Explains how those objects, properties, or features fit into a more generalized category.

Begins with the setting, how the term is used in the document(s) it is drawn from, or the audience it is aimed at.

Places that setting into the context of the category, or properties and features shared by other concepts or things like it.

Continues with what makes this concept or thing different than the other members of its category.

Begins by describing this particular concept or thing as a part of a greater whole.

Continues with the category that the greater whole fits into.

Adds what makes this concept or thing different than the other parts of the same greater whole.

Begins by explaining what the concept or thing does.

Continues by explaining how that role fits into a larger category with properties and other functions like it.

Begins with the category, or properties and features shared by other concepts or things like it.

Continues with what makes this concept or thing different than the other members of its category.

Provides additional classification, history, etc. about the concept or thing for elucidation purposes.

Begins with the category, or properties and features shared by other concepts or things like it.

Continues with what makes this concept or thing different than the other members of its category.

Continues with the theory of why this concept or thing fits into the category or why the differentiators are important.

Searching Google for a definition will almost undoubtedly return multiple definitions for the same term. And it isn’t just Google returning too many definitions. Many organizations that create glossaries for their documents are very sloppy with their terms – even the US National Institute of Standards and Technology!

Just because someone wrote a definition, that doesn’t mean it’s correct. Heck, if the United States’ own National Institute of Science and Technology can write some pretty bad definitions in their glossaries, anyone can write bad definitions in theirs.

Here are some forms for you to use when examining various definitions. We’ll use these forms to examine a few terms below.

Extensional Definitions

Lexical Definitions

Partitive Definitions

Functional Definitions

Encyclopedic Definitions

Theoretical Definitions

Testing termsIn researching terms relating to cybersecurity (a topic very close to our organization’s heart), we found that everyone agrees on what the definition of cyber means, but there are two different definitions of security, and eight definitions of cybersecurity. So let’s go through the process of analyzing their definitions using the rules for testing the definitions that we listed above. Testing Cyber

So we know that cyber works. The category works; the specifics work. Testing dictionary vs. glossary definitions of securityWe recently ran into two different definitions of security in two different glossaries. Both were much wordier than the dictionary definition of security. One, though wordy, was a good definition. The other, also wordy, had the wrong category altogether.

Testing definitions of cybersecurityMuch like the definition of security, we found multiple definitions of cybersecurity. It’s almost laughable that each and every glossary we encounter with cybersecurity in it, we encounter yet another different definition of the term. Let’s put the definitions to the test. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Analyzing definitions isn’t that hard. Look for the term to fit a general category. Look for the differentiators. Follow the other questions for each of the definition types. You’ll be fine.

There are three steps to follow for creating simple definitions.

If you can’t define the term in your mind to a single concept, then split the concepts into separate definitions. Think of report as both the sound of gunfire and calling the police to tell them about the sound of gunfire. That’s two definitions. One is a noun (the sound) the other is a verb (the act of calling or reporting). You have to define one concept at a time.

Here’s the scenario, you are writing whatever document it is and you’ve determined that you want to create a definition in your document. But your organization doesn’t have a definition for that term that you can draw from. So your first step in how to write a definition is to see if there’s a definition readily available that you can leverage (and cite so you aren’t plagiarizing).

The Unified Compliance team is in that predicament quite often. Where do we find the definitions? What methods do we use to look for them? Our methodology works its way down from the most authoritative sources to the least authoritative sources. From absolute definitions down to definitions you will have to build out yourself (following standards set forth by international committees).

You might have luck searching the Oxford English Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, or any other host of online dictionaries for single-word terms.

| Dictionary | URL |

| Merriam-Webster | https://www.merriam-webster.com/ |

| Oxford English Dictionary | https://en.oxforddictionaries.com |

| Cambridge | http://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/ |

| Dictionary.com | http://www.dictionary.com/ |

However, searching for phrases, especially technical phrases, won’t work really well with this list of dictionaries. For that, you’ll need to follow a different set of practices.

Here’s a couple of realworld scenarios for you from a technical document we were working with. The bolded terms are the ones you’d need to search for.

Use session lock with pattern-hiding displays to prevent access/viewing of data after period of inactivity.

Authorize remote execution of privileged commands and remote access to security-relevant information.

With these two sentences, we now have the following phrases:

Both Cambridge and Merriam-Webster found one of the terms listed above (remote access). However, none of them found the rest of the terms. Therefore, you’ll need to turn to searching more technical dictionaries and glossaries for phrases such as these.

| Dictionary | URL |

| webopedia | http://www.webopedia.com/ |

| TechTerms | https://techterms.com/ |

| Computer Dictionary | http://www.computer-dictionary-online.org/ |

| Free Online Dictionary of Computing | http://foldoc.org/ |

| Business Dictionary | http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/ |

| Investopedia | http://www.investopedia.com/dictionary/ |

| TechTarget’s Dictionary | http://whatis.techtarget.com/ |

| The Law Dictionary | http://thelawdictionary.org/ |

Even when searching the technical dictionaries above, however, only one term was found in one dictionary – “remote access” in webopedia. This means that you’ll need to turn to broader search engines, about 90% of the time. We’ll cover how to use search engines next. For now, if you were lucky enough to find the definition, save the URL. You will need to add it to the definition as the source of where the definition came from.

The bad news is that over 90% of the terms you are going to have to add to the dictionary are phrases that don’t exist in any known glossary or dictionary entry. As of this writing, most document authors fail to provide definitions for their key terms. Don’t worry yet, there’s one more search capability at your fingertips – searching Google’s definitions.

Here’s how to do it:

The last step is important, because you are looking for definitions written within a document and not in a glossary entry or definition of terms section. These definitions will be written within the context of the document’s content itself. Therefore, authors are most likely to state the terminology as saying, “X is this” or “many Ys are that”.

| Base Term | Single form | Plural form |

| session lock | define “session lock is” | define “session locks are” |

| period of inactivity | define “period of inactivity is” | define “periods of inactivity are” |

| security-relevant information | define “security-relevant information is”define "security relevant information is" |

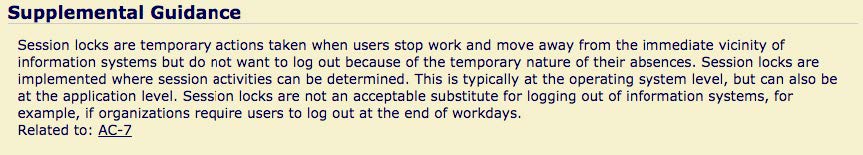

As an example, searching define “session lock is” turns up uses of the term, but no real definition of the term as shown in the diagram that follows:

However, searching for “session locks are” finds the definition in the very first search result Google returned, as shown below:

with the following definition

with the following definition

One of our researchers, Steven Murawski, adds that he has found some sticky definitions by typing "session lock" meaning or "session lock" definition. It only works about 10% of the time, but it is worth noting if you can’t find anything else. If you found the definition, save the URL. You will add it to the terminological entry as the source of where the definition came from.

This methodology works great for a few of the terms in our list. However, there wasn’t a single source that we searched for which had a solid definition for pattern-hiding display. So what do you do when you can’t find a source that specifically defines the term? You build the term’s definition following a well-defined international standard for doing so.

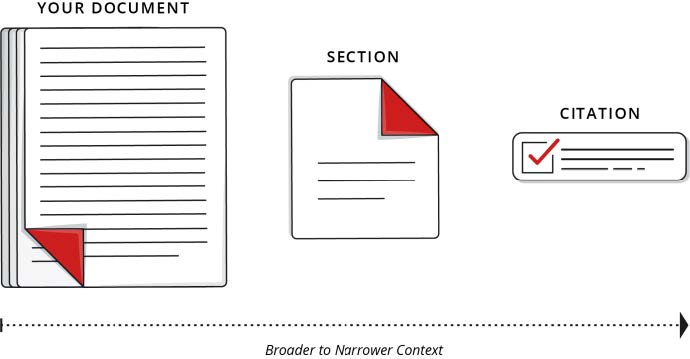

The first thing you need to do is to place your term into the proper context. If you are in a discussion and need to define your term, you’ll be thinking about the discussion you are having, and what types of concepts are being bandied about. If you are writing a document, you’ll probably need to narrow the concept down to one.

We’ll stick with you writing a definition for a document, and we’ll use the term pattern-hiding display. The document you are working with will form the subject field for the broadest context you are going to work with. The citation, no doubt, falls within a section of that document. And sections are broken down into various contexts within the document. Within that section, the Citation will provide the most specific context you are dealing with.

Now let’s look at the phrase pattern-hiding display within the context of the document, the Section, and the Citation it was found in.

| What | Context |

| Information Security Policy | Protecting Information |

| Section 3.1 | Using Access Controls |

| 3.1.10 | pattern-hiding displays protect information by preventing viewing of data |

From this, we know that the context is about hiding information from view as a form of access control that protects information. Got it.

We know from our document that pattern-hiding displays are covered in the section on access controls. So we are pretty certain that the general category for our term is going to be access control. But on looking up the definition for access control, we found that it can cover physical access, computer system access, and information access as well. So we have several subcategories of access control that exist.

So let’s start a worksheet for adding the term, the term’s possible category, and any possible subcategories that we know of. Then we’ll see if they fit.

| Term | Category | Subcategory | Fit? |

| pattern-hiding display | access control | physical assets | N |

| computer system | N | ||

| information | Y |

In our context, neither computer system nor physical assets fit our genus. Therefore, we know that the context we are dealing with is information access control.

But what type? That’s found in the attributes.

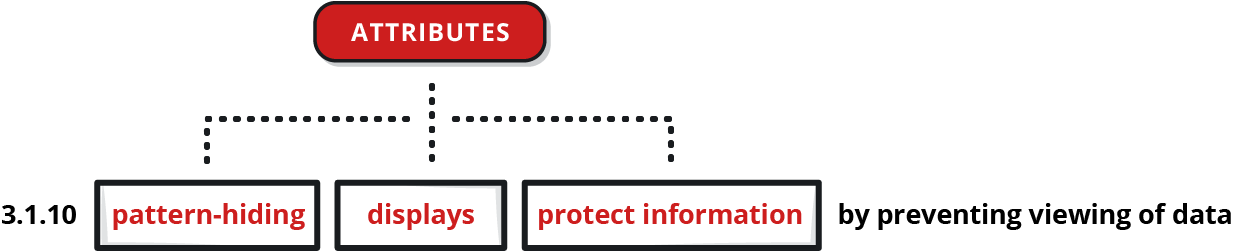

Now that you have the general category for the concept, you must examine the language for its attributes.

When we talk about attributes in this document, we specifically mean the distinguishing features as derived from the words used and the context in which they are used.

Because you are going to be dealing with terms you’ve found in a Citation, the attributes are really the individual terms you are dealing with within the context of the document you are working with. If you have two words in a phrase, you have two attributes. In our scenario, we have two words: pattern-hiding and display. Our attributes for this term are threefold:

We now need to search for each term in the various dictionaries and check to see if there are any definitions that fit our context of information access control that we are dealing with. Searching dictionaries for either pattern-hiding or pattern hiding produces nothing on its own. Searching the web for either one produces some rough definitions of algorithms and software methodologies to obscure numbers or images on a screen.

We now need to search for each term in the various dictionaries and check to see if there are any definitions that fit our context of information access control that we are dealing with. Searching dictionaries for either pattern-hiding or pattern hiding produces nothing on its own. Searching the web for either one produces some rough definitions of algorithms and software methodologies to obscure numbers or images on a screen.

| Term | Category | Subcategory | Fit? |

| pattern-hiding | session lock | Concealing information previously visible on a display. | Y |

| prime number | Artificial numeric patterns that are embedded with previously thought to be random numbers. | N | |

| screen saver lock | The capability, when the computer is locked, to set the screen to black or display selected or random images or numbers. | Y |

Searching for display gives us a bunch of definitions. One of which is a computer monitor, another of which is the process or facility of presenting data or images on a computer screen or other device. Within the context of the Citation and its section, we can conclude that the characteristic isn’t about the monitor per se, but about the ability to display data or images.

| Term | Category | Subcategory | Fit? |

| display | art | A performance or show. | N |

| assets | An electronic device for the visual presentation of data. | N | |

| computing | Process or facility of presenting data or images on a computer screen or other device. | Y |

We now have a comprehensive view of what our concept is and are one step closer to writing a good definition.

|

You need to start with the designation for the definition. You can’t define the concept unless you know what type of concept you are defining. Let’s put the research we’ve done into this section as a reference for our work here.

| Term | Category | Subcategory | Attribute |

| pattern-hiding display | access control | information | |

| pattern-hiding | session lock | Concealing information previously visible on a display. | |

| screen saver lock | The capability, when the computer is locked, to set the screen to black or display selected or random images or numbers. | ||

| display | computing | Process or facility of presenting data or images on a computer screen or other device. |

Designations are attributed to the concept you are defining, not the individual term.

Designations for definitions fall into two categories: parts of speech designations and named entity designations.

We will ignore named entities for now and discuss parts of speech. From our research here, we know that this isn’t a verb. It’s a noun. Simple.

| Term | Designator |

| pattern-hiding display | noun |

Now it’s time to go back to the cheat sheet. We listed seven different definition types. We are going to ignore all except the intensional definition because we are starting with simple definitions here. So we know that we’ll first be defining the genus of the term and then adding its differentia. We’ll do that in our worksheet for each of the attributes that we have.

| Term | Designator | Genus | Attribute |

| pattern-hiding display | noun | ||

| pattern-hiding | noun | session lock mechanism | conceals information previously visible on the display |

| noun | screen saver mechanism | sets the screen to black or displays selected or random images or numbers | |

| display | verb | computing | presenting data or images on a computer screen or other device |

This is really just a matter of putting everything together.

| Term | Designator | Genus | Attributes |

| pattern-hiding display | noun | A session lock or screen saver mechanism that | conceals information previously on the display by |

| setting the screen to black, or | |||

| displaying selected or random images or numbers. |

And there you have it, you have learned how to write a definition. A pattern-hiding display is a session lock or screen saver mechanism that conceals information previously on the display by setting the screen to black or displaying selected or random images or numbers.

There are six steps to follow for creating advanced definitions. The first three steps are the same as creating simple definitions, so we’ll skip these steps in the documentation that follows.

We’ve already covered how to write definitions, the communication of the concept of an instance we see or think about. We’ve covered some pretty basic rules about definition types and what should and shouldn’t be in them. Now we have to cover a few rules about how to express the term itself.

Why do we have to set rules?

Because many people who create glossaries are just plain sloppy (they probably don’t even make their beds in the morning). They’ll have plural forms. Capitalization where none is called for. Unconventional spelling. And – most egregiously – they’ll also include acronyms as terms themselves.

Ugh.

In order for modern electronic glossaries and dictionaries to work with Natural Language Processing engines, the following rules for entering the term itself should be followed.

If you aren’t aware, nouns and verbs have a base form and additional forms. Here they are:

| Base Form | Other Forms |

| Singular Non-Possessive Noun | Possessive |

| Plural | |

| Plural Possessive | |

| Simple Present Verb | Past |

| Past Participle | |

| Present Participle | |

| Third Person |

Here are the rules for both nouns and verbs.

NO acronyms should be added as terms, unless this is an acronym dictionary

Most nouns are pluralized by adding an –s to the end of a word. There are seven other pluralization rules that depend on what letter(s) the noun ends in.

Examples: cat – cats; car – cars; team – teams

Examples: church – churches; tax – taxes; pass – passes

Examples: elf – elves; loaf – loaves; thief – thieves

Examples: toy – toys; boy – boys; employ – employs

Examples: video – videos; studio – studios; zoo – zoos

Examples: baby – babies; country – countries; spy – spies

Examples: hero – heroes; potato – potatoes; volcano – volcanoes

NOTE: Irregular nouns follow none of these rules.

When adding verbs to the dictionary, ensure that you follow these rules:

Most verbs are conjugated by following these rules.

This rule excludes verbs ending in –ee. Verbs ending in –ee follow normal convention of adding –ing to the end.

NOTE: Irregular verbs do not follow the rules for past and past participle conjugation.

Verbs are considered to be irregular when their past tense and past participle forms are different from one another and those forms are not formed by adding -ed, -d, or -t to the base form. Here are a few irregular verbs.

| Verb | Past | Past participle |

| arise | arose | arisen |

| begin | began | begun |

| catch | caught | caught |

| do | did | done |

| fall | fell | fallen |

| go | went | gone |

| hide | hid | hidden |

| lay | laid | laid |

| lie | lay | lain |

There are great resources to learn more about irregular verbs online. One of them is here: http://speakspeak.com/resources/vocabulary-general-english/english-irregular-verbs

The next step to writing advanced definitions is to add semantic relationships to the definition.

Once you are finished with your definition you’ll need to place the new term into context with other terms. It allows your readers to see how terms interact with each other and allows Natural Language Processing Engines to relate terms together. It is the core of pattern-matching to harmonize regulatory structures to each other.

The following basic relationships have been taken from the Simple Knowledge Organization System’s (SKOS) Mapping Vocabulary Specification[1], as shown below.

They offer the ability to distinguish subtle relationships between two terms. As stated in the specification:

“Many knowledge organization systems, such as thesauri, taxonomies, classification schemes, and subject heading systems, share a similar structure, and are used in similar applications. SKOS captures much of this similarity and makes it explicit, to enable data and technology sharing across diverse applications.”

If two concepts are an exact match, then the set of resources properly indexed against the first concept is identical to the set of resources properly indexed against the second. Therefore, the two concepts may be interchanged in queries and subject-based indexes.

(Is inverse with itself.)

If “concept A has-broad-match concept B,” then the set of resources properly indexed against concept A is a subset of the set of resources properly indexed against concept B.

(Is inverse of has-narrow-match.)

If “concept A has-narrow-match concept B,” then the set of resources properly indexed against concept A is a superset of the set of resources properly indexed against concept B.

(Is inverse of has-broad-match.)

If “concept A has-minor-match concept B,” then the set of resources properly indexed against concept A shares less than 50% but greater than 0 of its members with the set of resources properly indexed against concept B.

(No inverse relation can be inferred.)

If “concept A has-minor-match concept B,” then the set of resources properly indexed against concept A shares less than 50% but greater than 0 of its members with the set of resources properly indexed against concept B.

(No inverse relation can be inferred.)

The problem in the SKOS model is relationships are limited to a single term or a single phrase. This model is great if you want to know that draft or chart is the same as map or not as broad as interpret. Basically, you are limited to three categories for practical purposes; broader, same, and narrower as shown in the diagram below.

What the SKOS and basic semantic relationship model doesn’t tell you is why interpret is a broader concept, or why scale is a narrower concept. What they don’t show are the linguistic relationships between the terms.

To extend the relationships past broader, same, and narrower, you’ll need a more advanced semantic relationship system. It should consider real-world relationships such as:

The illustration that follows re-examines the semantic relationships of the term map, shown above, using a more advanced set of semantic relationships. These relationships provide a much more robust understanding of connecting terms than a simple broader, same as, and narrower model can provide.

Advanced semantic relationships extend the model by adding linguistic and conceptual connections to each relationship.

There are many more relationships you’ll need to put into place if you want to provide greater context for your readers or Natural Language Processing Engine. Here are a few more of the relationships you’ll need.

Synonyms are broader than exact matches, as they extend the relationship to facts or states of having correlation, interrelation, materiality, conformity, and pertinence between concept A and concept B.

Antonyms then have enough variability, incongruence, and disassociation to be their opposite. The antonym is the inverse of the synonym and vice versa.

Included in the type of synonyms is metonymy, the semantic relationship that exists between two words (or a word and an expression) in which one of the words is metaphorically used in place of the other word (or expression) in particular contexts to convey the same meaning. Included in the category of antonyms are complementary pairs, gradable pairs, and relational opposites[2].

Complementary pairs are antonyms in which the presence of one quality or state signifies the absence of the other and vice versa. A couple of samples are single/ married, not pregnant/pregnant. There are no intermediate states in complementary pairs.

Gradable pairs are antonyms which allow for a natural, gradual transition between two poles. A couple of examples are good/bad, hot/cold. It is possible to be a little cold or very cold, etc.

Relational opposites are antonyms that share the same semantic features, but with the focus, or direction reversed. A few examples are tied/untied, buy/sell, give/receive, teacher/pupil, father/son, and open/refrain from opening.

A spigot and a faucet are two defined words that are exact matches, or synonyms, of each other. That’s an easy rule to implement. However, language is messy, and the uses of language within compliance documents are even messier. That’s why you must have advanced rules that go beyond synonyms for use cases (such as a personal data request being called a request for personal data, an information request from the data controller, or even a request for information on the processing of personal data).

To handle these types of use cases you must have a semantic rule that says “if the definition of a term-of-art matches the definition of a previously accepted dictionary term, the term-of-art should be considered an exact match and therefore be labeled a non-standard representation of the accepted term”.

The major and minor relationships described in the SKOS model are limited to linguistic parents and their children (or half-children as a minor match might be thought of). However, there are many relationships that are more specific that can and should be applied, especially when working with named entities and leveraging a Natural Language Processor’s named entity recognition engine.

By replacing the simple broader and narrower matches with more specific categorization, you can achieve structures like those employed by the Compliance Dictionary, as shown below.

| Relationship | Description | Examples |

| Linguistic Parent | Terms that are linguistically broader than the focus term, including origins of terms. | Term– Senior Systems Analyst |

| Linguistic Parent – systems analyst, senior | ||

| Linguistic Child | Terms that are linguistically narrower than the focus term, including derivatives. This is the inverse of Linguistic Parent. | Term - systems analyst |

| Linguistic Child - Senior Systems Analyst | ||

| Category For | A term of which the focus term is a kind of. | Term – tablet |

| Category For – portable electronic device | ||

| Type of | Terms that are kinds or examples of the focus term. This is the inverse of Category For. | Term – portable electronic device |

| Type of – laptop | ||

| Includes | Terms the focus term is an element of. It is the same as hyponymy. | Term – Personally Identifiable Information |

| Includes – mailing address, individual’s Social Security Number | ||

| Part of | Terms whose definitions are an element of the focus term. This is the inverse of Includes | Term – Personally Identifiable Information |

| Part of – privacy-related information | ||

| Used to Create | A term that is a template for or used to create the focus term. | Term – UCF Mapper software |

| Used to Create – Authority Document mapping | ||

| Is Created by | A term that comes from or is generated by the focus term. This is the inverse of Used to Create. | Term – system audit report |

| Is Created by – Secure Configuration Management Tool | ||

| Is Referenced by | A term that mentions or references the focus term. | Term – evidence |

| Is Referenced by – probable cause | ||

| References | A term that the focus term mentions or cites. This is the inverse of Is Referenced by. | Term – evidence |

| References – business exception rule | ||

| Used to Enforce | A term that uses the focus term to happen or cause compliance. | Term – configuration rule |

| Used to Enforce– system configuration | ||

| Is Enforced by | A term that uses the focus term to happen or cause compliance. This is the inverse of Used to Enforce. | Term – PCI-DSS |

| Is Enforced by – payment brand | ||

| Used to Prevent | A term that prevents the focus term. | Term – sanctions |

| Used to Prevent-– unauthorized data processing | ||

| Is Prevented by | A term that is prevented by the focus term. This is the inverse of Used to Prevent | Term – stealing |

| Is Prevented by– armed guard |

As of this writing, there isn’t a computer system that will automatically analyze terms, even in their context within a document, and determine what the relationships should be. At best, they are running between 40-45% accuracy[3]. This means you’ll want to manually ask yourself the questions, which isn’t really that hard[4].

Here’s our cheat sheet for you:

| Relation Type | Questions |

| Synonyms | Have you seen this term spelled differently? |

| Have you seen this term written completely differently (Personally Identifiable Information/individual’s non-public data)? | |

| Is this a metaphor for another term? | |

| Are there metaphors for this term? | |

| Antonyms | Are there any qualities of this term that signify the absence of qualities of another term (single/married)? |

| Could this term be graded on a spectrum (hot/cold)? | |

| Is there an opposite relationship of this term (tied/untied)? | |

| Category of | What terms fall under this category? |

| Type of | Are there any other examples of this term? |

| Includes | What does this term include? |

| Part of | Is this term a part of a greater whole? |

| References | Does this term refer to other terms? |

| Is this term referenced by other terms? |

By creating semantic relationships to your definitions, the reader will be able to understand how the term works with other terms.

[1] https://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/mapping/spec/ and https://www.w3.org/TR/skos-reference/

[2] “Linguistics 201: Study Sheet for Semantics.”

[3] Malaise, Zweigenbaum, and Bachimont, “Detecting Semantic Relations between Terms in Definitions.”

[4] Storey, “Understanding Semantic Relationships.”

The final step is reading your definition and making sure that it agrees with the word and the sense you are trying to define. Testing your definition on the format we wrote earlier.

In math, the substitution principle refers to the useful practice of replacing instances of a variable with a different variable. In definitions, it should be possible to replace a word in a definition by that word’s own definition without obtaining an unsatisfactory result[1].

For instance, if we were to use the substitution principle to examine covered entity, we would take the simple definition below:

| Term | Definition |

| covered entity | Healthcare providers who transmit health information. |

and replace key terms, such as healthcare provider, transmit, and health information.

| Term | Definition |

| covered entity | Healthcare providers [individuals and organizations that provide healthcare services] who transmit [to send or cause something to pass on from one place or person to another] health information [Any information, including demographic information collected from an individual, that: (1) is created or received by a health care provider, health plan, employer, or health care clearinghouse; and (2) relates to the past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual; the provision of health care to an individual; or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to an individual; and (i) that identifies the individual; or (ii) with respect to which there is a reasonable basis to believe the information can be used to identify the individual]. |

Verbose, but it works. The term doesn’t circle back on itself, begins with the category, and ends with the characteristics.

The verdict? It’s a good definition.

[1] Svensén, A Handbook of Lexicography.

We’ve established that in order to communicate clearly and effectively, we need to define our terms. Great. Got that out of the way.

We’ve covered what a definition is, and generally how it is formatted with both category and differentiator content. Coolio (which means really great according to Dorian’s nieces and nephews).

Now it’s time to look at how definitions are presented to people in writing. The scholars out there who talk about these things call all of these entries, collectively, terminological entries. And because we couldn’t think of anything easier to call them, that’s what we’ll call them too.

We are going to divide terminological entries into three types, from the least formal to the most formal:

Why custom dictionary entries? Simple. We, collectively, aren’t the editors of Webster’s or the Oxford English Dictionary. But we can be editors of other dictionaries, custom dictionaries.

Conversational definitions are those definitions wherein you write the definition into the normal discourse. A quick search of Wordnik (https://www.wordnik.com), the world’s largest online dictionary (as measured by numbers of words) run by Erin McKean, shows how they pick up and enter definitions through conversational entries.

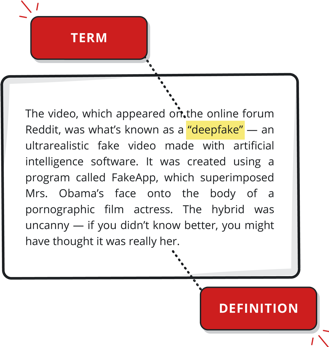

The term in question is deepfake. It was picked up by Wordnik and reported in their Word Buzz Wednesday blog entry, taken from the New York Times20. As you can see in the illustration below, the term deepfake was bracketed with quotes and then the definition immediately follows.

Through what we see here, conversational definitions have two parts; the term and the definition, without formally introducing either one, and without any cataloging of the terms.

To write conversational entries, follow steps 1 through 3 of how to write definitions.

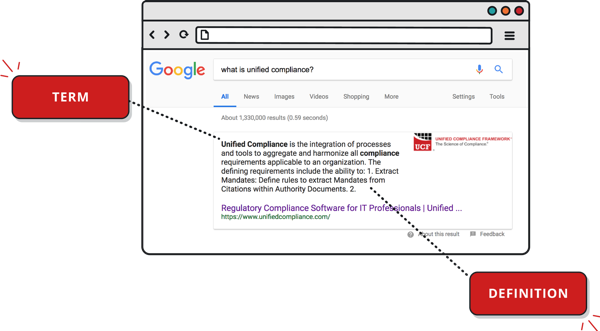

Google takes conversational entries one step farther. These are fantastic if you want to drive a point home to the search universe as our team at Unified Compliance has done with the answer to “what is Unified Compliance”.

When you search in Google with the phrase “what is/are XXX”, Google looks for either formal dictionary definitions of the term (first) and then if it can’t find one, will search for the most authoritative snippet of the term it can find. It then shows a search result in a special featured snippet block at the top of the search results page. This featured snippet block includes a summary of the answer, extracted from a webpage, plus a link to the page, the page title, and URL – as shown in the illustration below.

How do those get there?

When Google recognizes that a query asks a question, it programmatically detects pages that answer the user's question, and displays a top result as a featured snippet in the search results16.

Can you mark a page as a featured snippet so that Google can find it easier?

Sorry, Google programmatically determines that a page contains a likely answer to the user's question, and displays the result as a featured snippet. You can’t code your way into owning definitions. You can, however, be the authoritative source for those definitions if you write your snippet as a definition!

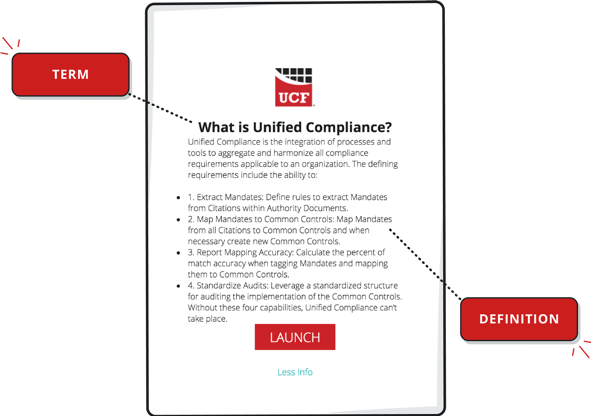

Here’s how the Unified Compliance team did it.

We wrote a page that we specifically designed to be a definition page for the term Unified Compliance. We wrote above the definition “What is Unified Compliance?”, thus asking the question. We then answered the question in the form of a conversational definition. We supplied the term first, “Unified Compliance”, followed by is (which acts as the separator between the term and the definition), and then followed that with the definition itself.

Like all good definitions, we began with the category into which the term fit, followed by the differentiators for the term. We even put bullet points in front of each differentiator for emphasis. The illustration above shows the page with the term and the definition called out.

To write snippet entries, follow steps 1 through 3 of how to write definitions.

There is a new methodology for technical authors who do not want to equivocate about what they meant when writing whatever technical document it is they are writing.

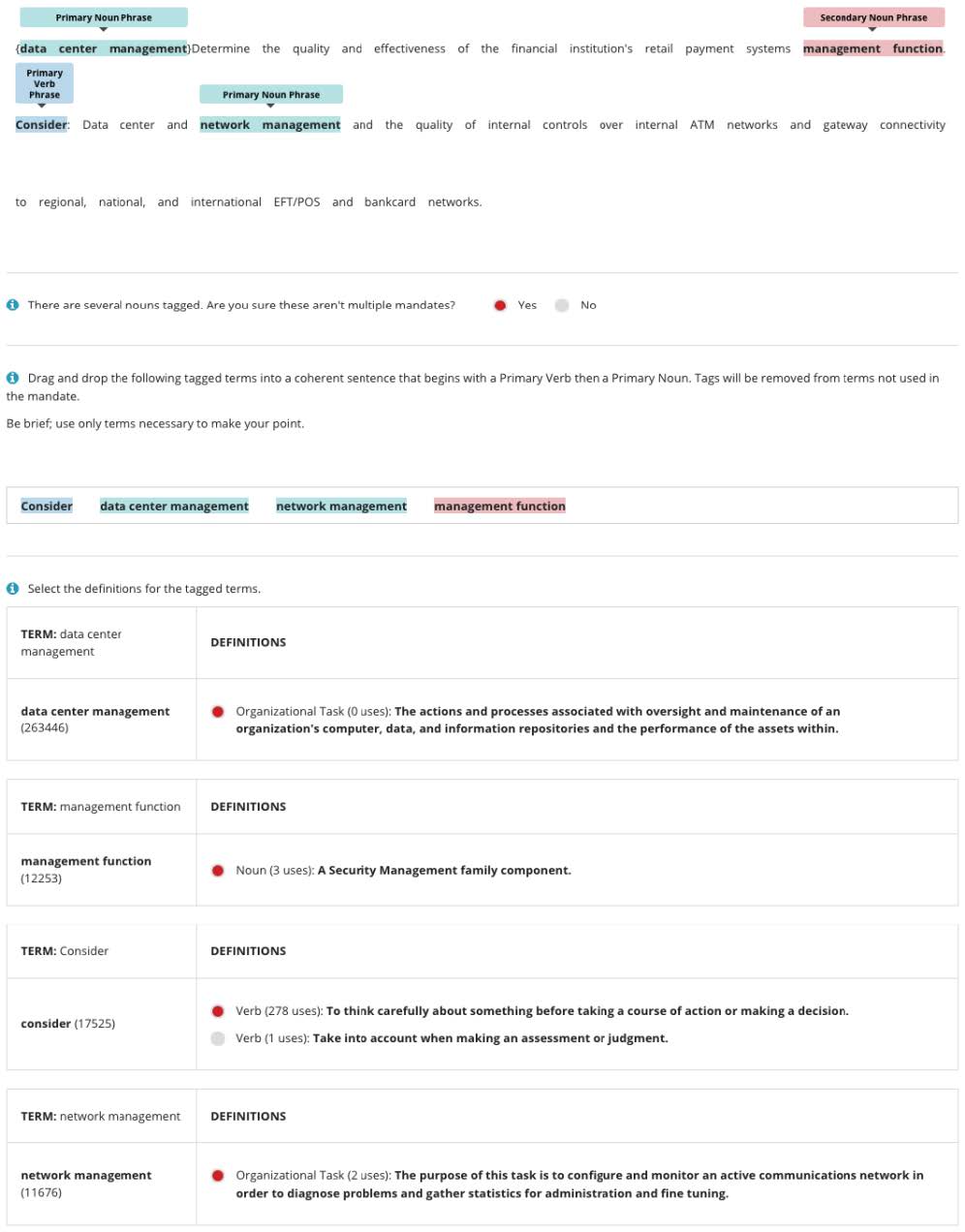

The Unified Compliance team has developed a verb and noun tagging and definition selection tool, shown below. The process is simple. When writing, the author tags the verbs and nouns they want to select definitions for, for that instance (knowing that terms such as report can mean many things, even within the same sentence).

Once the term has been tagged as either a verb or a noun, the system displays all of the definitions in the dictionary for that verb or that noun. Because the system is tied to an AI-based Natural Language Processing Engine, the system will automatically suggest the definition most used in the context of the sentence presented for tagging and matching.

Once the terms have been tagged and the definitions selected, the tagging is hidden to readers but exposed to computer systems. This can generate pop-ups showing the definition for the term as it was tagged by the author. Or, as is the case with each document the Unified Compliance team manages, the system can automatically create a glossary of verbs and nouns for the document in question.

This does, by the way, sometimes produce humorous results. One of our clients used the system to create a document written by multiple authors. The same term, only used six times in the document, had three different definitions selected. That’s because the different authors selected different definitions.

Since that point, we’ve changed the software so that once a definition has been selected in the document, it is a bit more insistent that the same definition be used in the same context. This is a great tool for technical documents, regulatory documents, etc. in that there is no equivocation about what the author meant for any verb or noun the author wishes to select a definition for.

Each word is tagged. Each definition is assigned. No doubt about what was meant. And the tagging and definitions follow the electronic format of that document forever.

For more information on using this tool, please contact the Unified Compliance team.

Dictionary entries have grown in complexity over the past several years due to the restraint of physical printing being removed. Originally, as John Simpson pointed out several times in The Word Detective22, definitions had to be as concise as possible, owing to the need to conserve printed space.

Electronic and online dictionaries don’t have such a restriction. Computer storage space, even on mobile phones, has grown exponentially year after year. The only restrictions on space now are those of the screen on which the dictionary is being presented.

Dictionaries will always have the first three categories of content, just like glossaries. However, given that electronic dictionaries are no longer constrained by printed size, many will have additional content that includes the various types of definitions.

Not every dictionary will have every item. Wordnik, for example, has most of these items, but doesn’t have the named entity recognition designators, or the advanced semantic relationships that go with them. ComplianceDictionary doesn’t have the reverse lookup, etymology, or visuals.

To write custom dictionary entries, follow steps 1 through 6 of how to write definitions.